Got an e-mail from Eveline Wawou this week - she represents artists that make art objects…

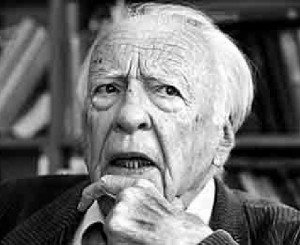

The relevance of the beautiful: Gadamer on art and play

In his essay ‘The relevance of the beautiful’, Gadamer explores the way aesthetic judgement in the arts enhances and enlivens our attentiveness towards the phenomena of the given world. Gadamer does not treat the question of ‘the aesthetic’ in the manner of the analytic tradition of modern philosophy, nor does he concern himself with individual aesthetic pleasure. His approach to the aesthetic experience is rooted in the phenomenological tradition: he is dealing with the place of art in our perception of the world.

Gadamer’s introduction of the concept of ‘play’ follows the precedent of Schillers ‘Letters on Aesthetic Education’. Both imply that aesthetic perception does not reside in the individual, but is part of something larger, is rooted in the relation between the individual and the society she lives in. This is why any shift in the way the individual relates herself to [the whole of] society effects aesthetic perception. Gadamer’s essay, page 7: “So long as art occupied a legitimate place in the world, it was clearly able to effect an integration between community, society, and the Church on the one hand and the self-understanding of the creative artist on the other. Our problem, however, is precisely the fact that this self-evident integration, and the universally shared understanding of the artist’s role that accompanies it, no longer exists.” The shift away from religion as a rationale for ordering society started in the nineteenth century. Since then, religion no longer constitutes a common ground for artists, their work and the art public. The idea that ‘play’ may constitute a new common ground, a new model for understanding aesthetic perception, is one that Gadamer argues with fervour.

Gadamer defines ‘play’ as a communicative act that has this one special feature: in play there are no passive viewers. People watching a game are more than just viewers: part of them participates in the game they are watching. We can see this happen when looking closely at the public that – for instance – is enjoying a football game or a boxing match. Gadamer states that to appreciate a work of art is likewise an active event, an act or a being in-play with the work, an act that one’s consciousness can surrender to and participate in. Full participation requires immersion, reduces and enhances perception to a point that it cannot be fully anticipated or controlled by the individual consciousness. Both the game and the work of art are forms of self-movement which require that the spectator play along with what they bring into being. Gadamer asserts the “primacy of the play” over individual consciousness: “the players are merely the way the play comes into being.”. Participation is never individual: a game takes both the player and the spectator out of herself and makes her part of a larger whole. A work of art is constituted in the moment the spectator takes up its challenge, in the ‘playing’ of the work. An autonomous event comes into being, something that stands in its own right and “changes all that stand before it” (page 25). The player / spectator does not only participate in the event that is the artwork, but she is potentially transformed by it. In this, he goes a step further than Duchamp, who with his famous quote ‘The spectator made the picture’ does refer to the ‘play’ between spectator and work but does not go into the possibilities of immersed perception and its potentially transforming effects.

Neither game nor artwork can be reduced to its intention, its materiality or the conventions surrounding it. It is the playing that draws spectator, player, intention, equipment and rules into the one event. This gives us an interactive viewe of art, and requires us to apply a different aesthetic structure to it, a structure that has little in common with the more standard accounts of aesthetic experience grounded in subjectivity. An artwork is not an object completely independent of the spectator yet somehow given over to the spectator for his or her personal enjoyment. To the contrary, the analogies with ‘play’ suggest that the act of spectatorship enhance or complete the work of art by bringing to fuller realisation that which is ‘at play’ within it. Both the spectator and the artist play a crucial role in developing the ideas that art activates. The spectator is immersed in her experience of art, absorbed in its play and maybe even transformed by that which her spectatorship helps to bring into being.

| « Conversational ping-pong | <-- previous post | next post --> | Casco: Come Alive! » |

|---|