Have been inspired by this blog's subtitle - Everdien's external memory - to look into…

Anti-oedipus

Posted by Everdien on 1/06/11 • Categorized as All posts

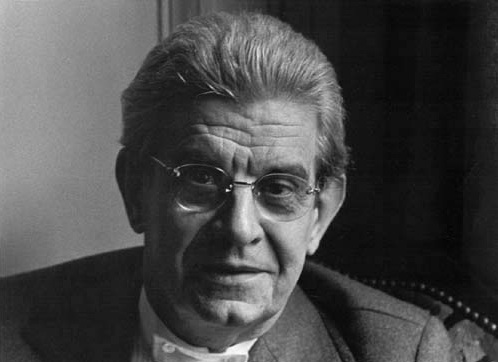

Am studying the work of french psychoanalist Jacques Lacan – heady stuff. It came about because I became interested in the game of hide-and-seek and the motives for playing this particular game. I have this idea that hide-and-seek could be a manifestation of the unconscious desire go back into the womb: a desire to re-establish symbiosis. Am working out a way to channel this insight into an installation – will blog about that asap. But first I must document Lacan’s take on the desire to reverse the process of becoming ‘me’.

This is what Lacan has to say about this desire, words taken from the exellent lectures about him on a turkish site that for the rest I can make head nor tails of.:

1. Lacan is known as the French Freud. This summarises rather well what he did, which is to translate Freud into French. It’s a very very free translation.

2. For Lacan as for Freud, a child is born into desire. Desire, désir, is what makes the psychic machine work. But for Lacan this desire is more than sexual, though it is also sexual. To explain that I need to explain one of Lacan’s key concepts: the real, la réelle.

3. The crucial point is this: we cannot experience the world directly. All we can experience is a mental event. I touch the table, or see a friend, and think I am experiencing the table or the friend directly. This is not true. I see or feel some phenomena, and interpret them, and what I experience is the interpretation: friend, table. That is the only way I can know the world. I can’t get behind the interpretation to experience the world direct, raw, unmediated.

4. The interpretations, that are all I can know of the world, are made up of two things: language, and images that I have previously experienced: previous interpretations. They are not real. They are mental events. Experience = images + language.

5. Both language and images, says Lacan, are false. All these mental events that I perceive are approximations, makeshifts.

6. We cannot perceive raw reality. Whatever raw reality is like, and I cannot possibly imagine what it might be like. Lacan says that though we cannot know the real, la réelle, in any way whatsoever, we have an obscure sense of it, of its plenitude, its incredible fullness and richness. We want it. Desire, for Lacan, comes out of the imbalance between what we perceive, language and images, and what actually is: la réelle. This enormous discrepancy is the primary fact of our mental life, like a constant imbalance or vertigo. This, not eros, not sexual desire, is the main thing that motivates everything, for Lacan .Of course if we could somehow actually encounter the real, without any conceptualisation coming in between, it might be blissful, or it might be actually terrifying. It would be like meeting God, face to face.

7. It is impossible to satisfy this desire, because we cannot know what we want. The real is utterly unknowable. Everything gets in the way: all the mental events that make up our false view of the world. We can’t even really long for what we long for; we are fundamentally confused.

8. So this longing is displaced: we long for everything else instead. Sex and food and consumer objects, trying to fill the void of desire. But we are not satisfied by any of these things, because as soon as the desire is fulfilled it vanishes, becomes, strangely, unsatisfactory: no, I think, that’s not it, that’s not what I wanted. Soon another desire arises: maybe that’s it, maybe, maybe, and so I long for that instead. Until it too is satiated and falls away. And so on for ever.

9 We are born too soon. It is generally admitted that human beings come into the world too early. Some say it’s because of our big brains. Big brains need big heads, and if we stayed in the womb any longer these big heads would, like Alice, grow too big, and wouldn’t be able to get down the birth canal. We are all prematurely born: most animals emerge from the womb with considerable functionality, able to feed, to walk, to be independent to some degree of their mothers. Humans emerge helpless, completely dependent on their mothers: as if, for months after birth, they are still in the womb, still part of the mother’s body.

10. In the beginning, the child (of either sex: note this) has no language, and no images, and so knows no concepts or distinctions. There is no difference felt between child and environment, and in particular between the child and the source of nourishment, the bottle or the breast. The world has no categories for the young child: it is not divided. It is as if the baby is still in the womb. The sense of self in the child is absolutely synonymous with and completely identified with his or her universe.

11. We adults are not like that: we all have a very clear and constantly maintained distinction between the sense of “I” and the rest of the world. The world begins immediately at the outside of our skin, and goes on for ever, containing millions upon millions of separate things, that are none of them us. Cats and cows and chairs and cheese and all those other myriad things the world is so full of. For the child, the world is full of only one thing; there is no boundary at the skin. The self and the others are one. This experience, for the child, resembles the richness of the real. It is not the same, but it is like it, and therefore satisfying.

12. But simultaneously there are phenomena that keep happening that contradict this, because the child isn’t in fact in the womb: it is aware of unpleasure, and pleasure: of pain and hunger and the food not being there. So the first thing that we have to do is to make a distinction between the self and the world: to aquire a self-image. Lacan summarises the process in a symbolic event: the mirror phase, le stade du miroir.

13. Once the child has acquired language and realised the multiplicity of things then the original sense of oneness with the mother, and the even deeper desire for the real, is lost. No, not exactly lost: they become unconscious, because they are outside language. Once we begin to think in language, it’s hard to imagine what it is not to have it: it is unspeakable. It is unconscious. So we have not only lost something wonderful, something important, but also we don’t know, we can’t possibly know, what it is that we have lost, because we can’t express it in language, because it is not in language: it is, exactly that which language is not. L’imaginaire can surface in dreams and fictions, but desire itself, desire for the real, is deeply deeply hidden.

14 And here, for Lacan, is the root of suffering. In each of us there is an absence that we cannot, by definition, think about, because we cannot name it. At the moment of the creation of the ego, the self, an absence is created. It is an absence as big as everything, because it is caused by the removal of a sense of unity with everything. But that removal created ‘me’, gave birth to my sense of self, so ‘I’ can’t get back to it, because to do so ‘I’ would cease to exist. And so what I want, I can’t have. What I do is to try and fill this gap up with things, with all of the things that I might think I am hungry for, like food and toys and books and cars and houses and computers, and all the other goods, that seem so good, in anticipation, but, when attained, seem to do no good at all, because the absence is not filled.

15, One of the ways you can read Lacan’s reading of Oedipus is to say that it is a critique of patriarchy. Lacan was deeply suspicious of repressive masculine authority, of any way of using language to tie down knowledge, to repress freedom. He called it père-version, remember. He also called it le discours de l’université. Men traditionally in this culture see women as illogical, dreamy; women see men as excessively rational, oppressive. Lacan says that both these ways of being, the symbolique and the imaginaire, are there in all of us; and he appears to value the imaginaire over the symbolique.

Gerelateerd:

-

Unconscious Memry

-

Some notes about desire

The nation-state and the "marxist" ideological apparatuses connected with it (parties, cells, unions, and other…

| « Hop on | <-- previous post | next post --> | Before blogging » |

|---|