In his essay ‘The relevance of the beautiful’, Gadamer explores the way aesthetic judgement in…

The relevance of the beautiful

My garden is very beautiful these days – the wisteria drapes its garlands around the balustrade, scenting the air with nostalgic sweetness. The tulips are blooming and columbines pop up at unexpected places. It is of course impossible to completely functionalise beauty, but the question is pertinent: what relevance does beauty have?

The Relevance of the Beautiful

“So long as art occupied a legitimate place in the world, it was clearly able to effect an integration between community, society, and the Church on the one hand and the self-understanding of the creative artist on the other. Our problem, however, is precisely the fact that this self-evident integration, and the universally shared understanding of the artist’s role that accompanies it, no longer exists – and indeed no longer existed in the nineteenth century.” (1)

‘A problem that bestirs us to exceed ourselves is beautiful.” (2)

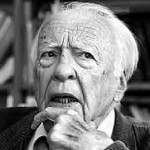

Hans-Georg Gadamer (1900 – 2002) was a German philosopher, best known for his treatise Truth and Method (1960). His essay The Relevance of the Beautiful is subtitled art as play, symbol and festival. It deals primarily with the place of art in our perception of the world – a phenomenological approach. Gadamer wants aesthetic pleasure to lead us to a greater degree of attentiveness to and involvement with the world around us. “Because of the beautiful we succeed, in the end, to re-connect to the real world.”(3)

Like Huizinga, Gadamer states that play is an elementary function of human life, and that human culture without a play element is unthinkable. He stresses that not only the players, but the spectators too belong to the game. Both can give themselves up to it – which becomes abundantly clear when we watch the way football fans in the stadium immerse themselves in a game.

Important in Gadamers thinking is the concept that modern art must break through the distance that has come into being between the artist, the work of art and the public. Where religion used to be both common ground and common purpose, since the nineteenth century this common denominator has been abandoned. ‘Play’ is proposed as a new model, a new common ground. A work of art is to issue a challenge to actively engage with it, but also to leave room for players to take up this challenge. The work should claim an answer, an answer that can only be given by those who take up the challenge the work poses. And this answer is to be an individual one, brought about by playing the game the work of art proposes. “The player belongs to the game” (4).

Art, played like a game, demands a surrender of consciousness and an immersion that cannot be anticipated beforehand. Play is proposed here as taking the place of religion because of its potential for transcendence. : “they both .. provide experiences of ‘otherness’, ‘alterity’ or ‘altered states of consciousness” (5).

Proposing play as a common ground, Gadamer makes clear that artist, work and public are to be part of a single game, a game that cannot be controlled beforehand and that exceeds the normal boundaries of perception. What really happens when a work of art takes one up? One must play along, give oneself up to it, respond to its proposition. In Gadamers way of thinking, the effect of a work of art is not created by the artist at its conception, nor is it defined by its formal characteristics, but it exists in the moment of and by the intensity of the public’s engagement with it.

In this, he is in complete agreement with Duchamp, who in his famous 1954 Houston lecture on the creative process, stated: ”All in all, the creative act is not performed by the artist alone; the spectator brings the work in contact with the external world by deciphering and interpreting its inner qualification and thus adds his contribution to the creative act. This becomes even more obvious when posterity gives a final verdict and sometimes rehabilitates forgotten artists.” (6)

In his book ‘Relational Aesthetics’, Bourriaud carries Duchamp’s reasoning further forward. Under the heading ‘The work of art as a partial object ‘ he states:”This type of [non-discursive] knowledge is only possible provided that we do not see mere delight in the contemplation of the artwork.” He links Guattari and Nietzsche to this train of thought: “Guattari prowls in the vincinity of Nietzsche, transporting the vitalism of the German philosopher. ”

This new take on ‘the beautiful’ suggests that aesthetic appreciation is active, more active than words like ‘surrender’, ‘immersion’ and ‘giving up’ suggest. As dinner guest and speaker at MaHKU symposium ‘Doing Dissimination’, Bourriaud enlarged on his topic and took the game of tennis as a metaphor for the relation between artist, work and public: “The artist serves, the public returns the volley. Different strokes, same game.”

(1) Hans-Georg Gadamer, The Relevance of the Beautiful, page 7

(2) Nietzsche as quoted by Nicolas Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics, page 99

(3) Hans-Georg Gadamer, The Relevance of the Beautiful, page 16

(4) Hans-Georg Gadamer, The Relevance of the Beautiful, page 34

(5) Brian Sutton-Smith, The Ambiguity of Play, page 66- 67

(6) http://www.wisdomportal.com/Cinema-Machine/Duchamp-CreativeAct.html

| « Algorithmic approach and free-form play | <-- previous post | next post --> | Romanticism as a life raft » |

|---|